The Chimp-Pig Hypothesis

This first part is true, regardless: we often think of things as true-or-false, yes-or-no, always-never. Often (see what I did there?), we'd be better off with more nuanced thinking.

One example is the idea of fertility. We tend to think of fertility as a yes/no concept: the common definition of a species is "the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes can produce fertile offspring."

But even a little thought about humans should show this isn't really an absolute; it's more probabilistic at every step of the process. No particular sexual encounter is guaranteed to lead to a pregnancy, let alone a baby, let alone an adult, let alone an adult who can conceive.

In humans, approximately 85% of couples who are trying to conceive will be able to get pregnant; about 20% of pregnancies will miscarry in the first 20 weeks; a share of those babies will tragically die at childbirth; and 10% of those children will themselves grow up to be infertile. When we say "two individual humans can produce fertile offspring," what we mean is more like "two individual humans (within a year of trying) can produce fertile offspring roughly 3/4th of the time."

The same is true from the other direction: when we say two animals "can't produce fertile offspring," that should be more probabilistic and less absolute.

If you're like me, the only real-life animal hybrid you vaguely learned about is the mule: half-horse, half-donkey, and (so we were told) infertile. It turns out, this is untrue: there are documented cases of mules getting pregnant going back to Herodotus (and going up to modern animals who could be genetically tested and confirmed).

Again, it's our yes/no absolutist thinking that leads us astray: mules are far less fertile than (say) a pairs of humans, but rather than saying they're "infertile" we should just say "less fertile".

Interestingly, it generally tends to be easier for a mule to have a baby if you "backcross" a female mule with a male horse, rather than breeding two mules. And if a mule mom and a horse dad have a mule-horse hybrid baby, the same thing repeats: those hybrids are also less fertile than humans (or horses, or donkeys), but probably more fertile than mules. Given enough time and enough horses/donkeys/mules, you could theoretically breed a line of almost-horses with one donkey ancestor.

[Fun but tangential facts: (mammalian) hybrids tend to prefer to mate with their mom's species than their dad's; (mammalian) female hybrids tend to be more fertile than mammalian male hybrids].

Mules, by the way, have many great features. They are "more patient, hardier and longer-lived than horses," and "are perceived as less obstinate and more intelligent than donkeys." They eat cheaper food than a similarly-sized horse, and have tougher hooves and more stamina. For this reason they were bred and used in Egypt 5000 years ago; they were also featured in the Illiad and the ancient Hebrew Scriptures.

I don't want to get personal here, but: were you featured in the Illiad or the ancient Hebrew Scriptures? My point is, mules are great and (specifically) they have various advantages exactly because they're hybrids, combining the best traits of mom and dad (as many of us hope to do). Keep that in mind for a moment....

In this post, I'm going to tell you, as best I can, an idea about evolution that many of my friends find (to say the least) outlandish. (You can read the full original argument from Eugene M. McCarthy at http://macroevolution.net/; any mistakes added are of course my own).

I'm not very knowledgeable about genetics, and I can't really vouch for how plausible the hypothesis is. (But note: on the same grounds, I can't really vouch for how plausible Darwinian evolution is).

My interest is actually in something else: what does it feel like to have your beliefs overturned? You know the story: as was true for every previous generation, some of the things we believe today must be entirely wrong, and yet very few of us ever make a 180 on anything. It's easier to accept we must be wrong about something than to actually admit we are wrong about anything. Which ought to worry us.

I'm frankly more interested in moral wrongs than scientific one. But the tricky thing is that successful moral revolutions are so complete that once they're over we struggle to imagine how anyone ever believed the abhorrent previous thing. (Kazuo Ishiguro is the only person I know to have actually captured what this probably feels like, but my co-blogger and I also made an attempt in this piece for WIRED).

To me, the Chimp-Pig hypothesis is a rare theory that is 1) internally consistent and coherent enough not to be ridiculous, 2) overturns everything we think we know about a major area of knowledge, and 3) doesn't have any meaningful implications for our current lives, so it won't really hurt anyone if you give it some credence and it turns out to be false.

Which is all to say: to me, the most interesting interaction you can have with the Chimp-Pig hypothesis is to let yourself believe it, at least briefly, and then observe what it feels like to have your world overturned. The Chimp-Pig hypothesis may or may not be one of the great revolutions of your lifetime, but I think it's one of the best practice cases I've ever seen. And when your real moment of truth comes, it'd be good to have some practice.

If you've ever been to a primate family reunion, you might notice that we humans are the odd ones out.

The most obvious difference is of course our relative hairlessness, but there are other big differences too.

You'll notice our cartilaginous noses stick out (haha) compared to all the other primates with their little flat nostrils.

While walking over to the drinks table, you might well notice that our gait is very different from other primates: the primates can't extend their knees and lock their legs straight, so they can't walk the way humans do (as King Louis in The Jungle Book would sadly explain).

Meanwhile, the other primates all have a layer of muscle directly below the skin that lets them independently move the skin all over their body, so e.g. they can twitch to scare off flies. (We only have this ability in our necks and faces – without it we couldn't generate facial expressions).

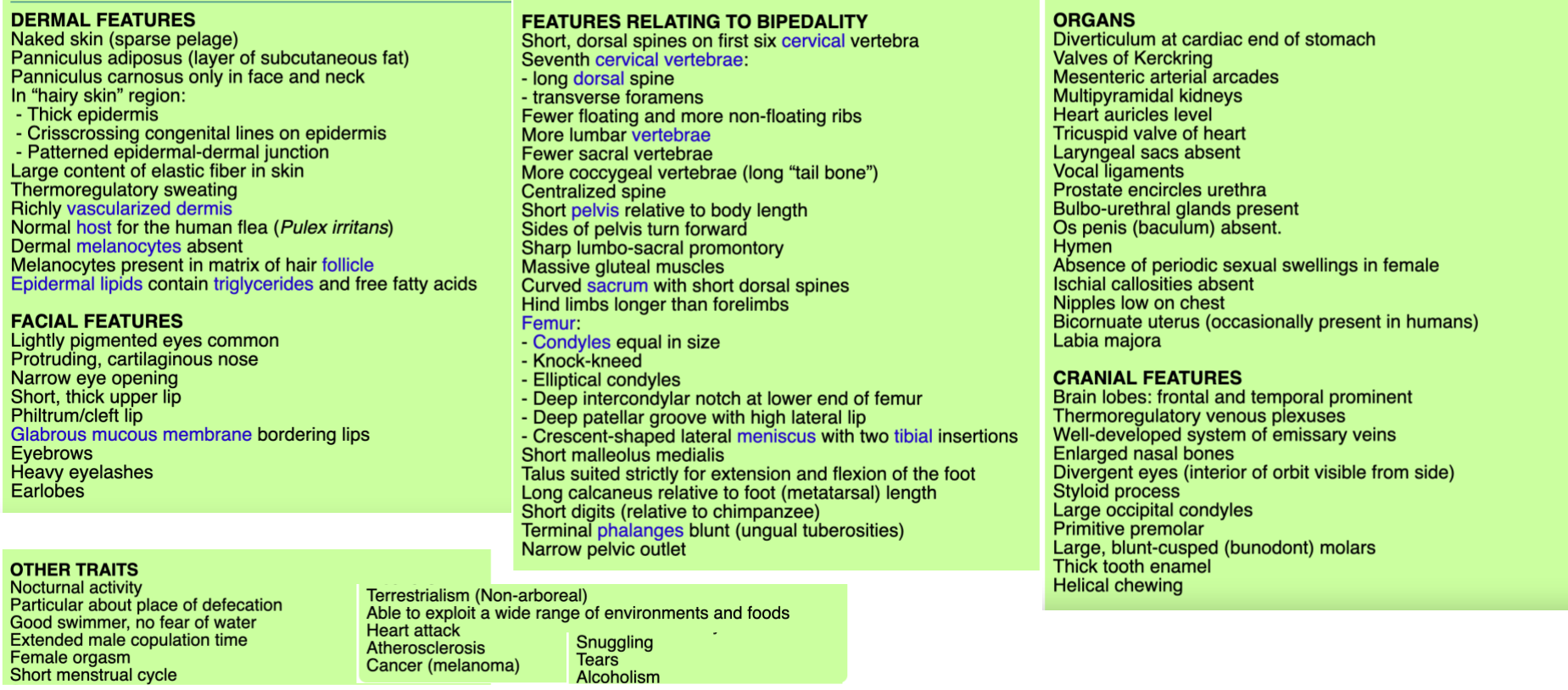

If you were so inclined, you could make a whole list of Human Traits Not Seen In Other Primates, to whit:

We're unquestionably primate-like – 99% similar, so they say – and, hey, it's the differences that make the sameness exceptional. But still, our differences from primate seem to have ultimately led to our line completely taking over the world. That seems worth investigating.

Incidentally, there's one other animal that exhibits all the traits on the list above – it's relatively hairless, has a cartilaginous nose, can lock its legs straight, has a layer of fat below the skin, etc etc etc. I'm sure you can guess....

The Chimp-pig hypothesis is that humans might be hybrids of a pig and some chimps. Like the mules we talked about earlier, the original chimpig would have back-crossed into the chimp family, giving birth to some chimpchimpigs who then mated with other chimps to create chimpchimpchimpigs, until a stable species developed that was largely chimpy but slightly piggy. (Side note: I'm saying "chimp" and "pig" for simplicity, and "chimpig" because it's funny, but it could be some other chimp-like and some other pig-like).

Like mules, this new line of animals had some great features from both pigs and chimps, so much so that we became the world's new boss-type. Many generations later, I'm sitting at a laptop typing this sentence and you're sitting at some other device reading it.

Allow me a brief digression for an analogy about how we can infer evolutionary histories. Imagine you hear Swahili for the first time, and you don't know anything about its history or origins. You slowly realise that 5% of the words in it sound like words you know from English.

How would you figure out whether this was convergent evolution, coincidence, or actual direct influence (whether from English to Swahili, or Swahili to English, or from a shared mutual ancestor to both)?

Convergent evolution does happen in languages, sometimes: both Swahili and English use mama for "mother", and many different languages have independently ended up using mama for mother, since it's one of the first sounds that babies are able to make. If multiple languages independently develop the same words through convergent evolution, they'll end up sharing similarities with no direct casual influence.

Secondly, coincidence is always possible, and with enough words to choose from it's effectively inevitable. The word gari sounds a bit like car, but not enough that you should be confident they have the same root, since it could be (and in this case is) a coincidence. Simply picking a few words from Swahili that have similar-sounding words in English and declaring the languages connected can rightly be condemned as cherry-picking.

But when you look at Swahili words like antibiotiki or buldoza – words that I don't even have to define for you, because they mean exactly what you read them to mean–it's much less likely it's just a coincidence. The more highly-specific words you can find that are exactly alike in both English and Swahili, the more you should suspect that there's a direct connection between those languages.

Now let's imagine a whole imaginary language family, Panian, in which all the constituent languages are mutually intelligible: some of the words are pronounced differently in different variants, but every language in the family has basically the same words with slight variations.

Except that in one of the languages – let's call it Sapien – 2% of the vocabulary is completely different from anything in every other Panian languages. An anthropologist studying Panian makes a list of all the words in Sapien that differentiate it from other Panian languages, and – only then, with the complete list in hand – she investigates which other languages contain those words. She discovers that every single one of them is an exact match for a word in a non-Panian language, Sussian.

What do we infer from this? Surely the most likely option is that Sapien is actually a hybrid of (a lot of) Panian with (a little bit of) Sussian.

Languages are obviously different from life forms – for a start, convergent evolution is going to be far more common for life forms, because there's a very good reason for multiple different animals to develop (say) a crab-shaped body, but there's no good reason for multiple different languages to refer to those animals as "crabs".

Still, the general evolutionary logic is the same. If someone pointed out a few random features of humans, and then pointed out that some other random animal shares those cherry-picked features, you shouldn't be very impressed – in fact, this is comically easy to do. (E.g. whales also have a layer of fat directly below the skin; that doesn't mean humans are closely related to whales).

But if someone goes through a primatology textbook and makes a list of all features that are shared among primates except humans, and then goes through other animal textbooks and finds that every one of those features is shared (in a detailed, specific manner) with one specific, non-primate animal, you've got a much stronger hypothesis – not a watertight proof, but a hypothesis worth investigating.

There are two main objections I've gotten when talking about this whole pig-chimp thing.

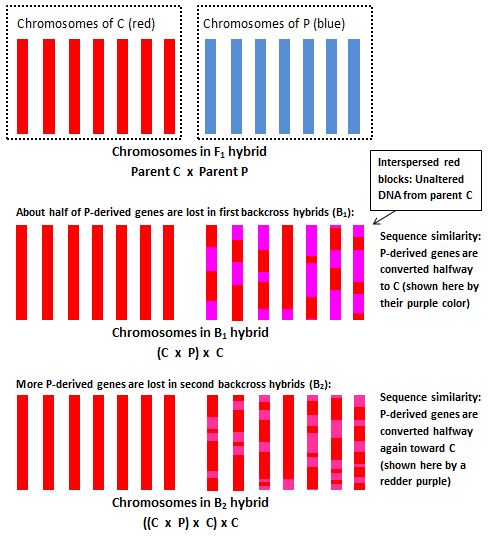

First, shouldn't it be easy to tell from DNA whether our ancestors were pigs or not? Unfortunately, no. The way that sexual reproduction works, while matching up the DNA strands from mum and dad to create a new double-helix for baby, the system "converts" any non-matching base pairs to make them align. The result is that even after a couple of back-crosses we won't find clear segments of pig DNA to point to. (You can find the technical explanation here, search for "genetic data").

The second objection I often get is that chimps have 48 chromosomes, pigs have 38 chromosomes, and it's not possible (so my interlocutors think) for animals with such different karyotypes to mate. But this just means that they're sadly unfamiliar with the Zorse: part Zebra (44 chromosomes), part Horse (64), entirely zorsome.

This all goes back to our initial exploration of fertility: it's certainly true that animals with very different karyotypes are less likely to produce fertile offspring than animals with a shared karyotype. But if you throw a million monkeys at a million typewriters for a million years you'll eventually get Shakespeare, and if you throw a million chimps at a million pigs... well, in a different sense you'll eventually get Shakespeare.

You may well have other objections and counterarguments. If there's enough interest I will write up another post discussing those, or you can just go straight to Eugene McCarthy's original and incredibly detailed argument here:

But let me return briefly to my original motivation for this piece. Many people I've told this theory to have an immediate negative reaction to it, and jump straight to those objections with such speed that it doesn't seem possible they're really weighing up the evidence.

And I think this is a shame. As I said earlier, I think the Chimp-Pig hypothesis is a great way to flex your muscles at having a deeply-held belief challenged (in a context where it doesn't ultimately matter); I think sitting with the discomfort this hypothesis generates is a useful exercise by itself, because I suspect it's the same feeling you would have the day you first heard some deep moral truth that (should) topple the framework of your existing beliefs.

And part of our problem, I suspect, is another thing we're not usually nuanced enough about: degrees of belief. Your available options here are not simply "immediately switch to believing the chimp-pig hypothesis" or "immediately reject the chimp-pig hypothesis"; you could instead move from having 0% belief in it to having (say) 10% belief. That option is open to you, to all of us, for this and for everything else in life. And I'd like to suggest it's a pretty damn good one.

Because it's 2023, I'm legally obliged to end this piece by asking DALL-E for some images of "chimp-pig hybrids" doing various human activities. One friend of the blog said she'd be 5% more convinced about the argument after seeing these, so:

You're welcome.