Intrauterine Devices

It’s not cold or flu season, we’re in between pandemics, and sports physicals haven’t started, so our primary care clinic schedule is a little bit slow and we spend a lot of time chatting.

One topic that always generates a lot of discussion (second only to “do we deserve Starbucks today”) is IUDs - while our providers place IUDs occasionally, members of our office staff (including one who previously worked in an OB/Gyn office) swear vociferously that they would never consider them for themselves.

The passion inspired by discussions of IUDs isn’t unique to our medically inclined workplace - IUDs generate a lot of strong opinions and are reliably engaging party conversation fodder. While I’ve had friends occasionally tell me how much they love their IUDs, horror stories about challenging placement and removal are just as common.

If you look at the patient-directed resources, you’ll be struck by the unrivaled benefits of IUDs. Planned Parenthood and Kaiser Permanente feature them at the top-center of their page on birth control options, pointing out that they are “Low Maintenance” and “99% Effective.”

Similarly, Mass General’s patient education website about IUDs cites Dr. Katherine Pocius of Harvard Medical school in saying, “IUDs are an increasingly preferred method of birth control for women of all ages. Dr. Pocius generally recommends an IUD for most women interested in contraception.”

So, it’s remarkable that so many women feel so negatively about them compared to other birth control options.

What are we talking about then?

Generally the idea of an IUD is that you put something in the uterus that makes it harder for sperm to reach the egg or for a pregnancy to implant. Like much of the practice of obstetrics and gynecology, the IUD developed in an inauspicious context (interwar Germany) and involved some trial and error: there was a silver-containing model which turned patient’s gums blue, and a later version which funneled bacteria into the uterus. Modern IUDs are fortunately much safer (and better tested).

Right now there are two kinds of IUD in use. The copper IUDs disrupt the ability of sperm to swim through the uterus and reach the egg. It doesn’t have any hormones, so it’s a preferred choice for women who are breastfeeding or otherwise want to avoid extra hormones.

On the other hand, hormonal IUDs both thicken cervical mucus (making it hard for sperm to pass into the uterus), disrupting the uterine lining, and can sometimes prevent ovulation, depending on the dose of hormone in the device.

(Neither type of IUD causes an abortion - expulsion of an implanted pregnancy - although this mistaken belief is held by about 17% of doctors.)

Functionally, either type of IUD is equally effective, with about one pregnancy per 200 women per year. This is about the same birth rate as tubal ligation, and just a little worse than the Nexplanon implant, which only has about one pregnancy per 1000 women per year. For comparison, birth control pills result in about one pregnancy per 14 women per year, and condoms have a failure rate of one in eight women per year.

And the rate of serious complications is pretty low - a risk of 1 in 325 for uterine perforation, and a little higher for spontaneous expulsion. So it’s not wrong to say that IUDs are safe and effective!

But stories of negative experiences abound. These tend to focus on entirely different aspects of the devices than “did you get pregnant” and “did you need a surgery to repair a hole in your pelvic organ.” Common complaints are that IUDs are uniquely uncomfortable to insert, they can cause significant post-insertion side effects, and there is a lot of overall hassle in arranging for placement and removal.

Rich Innervation

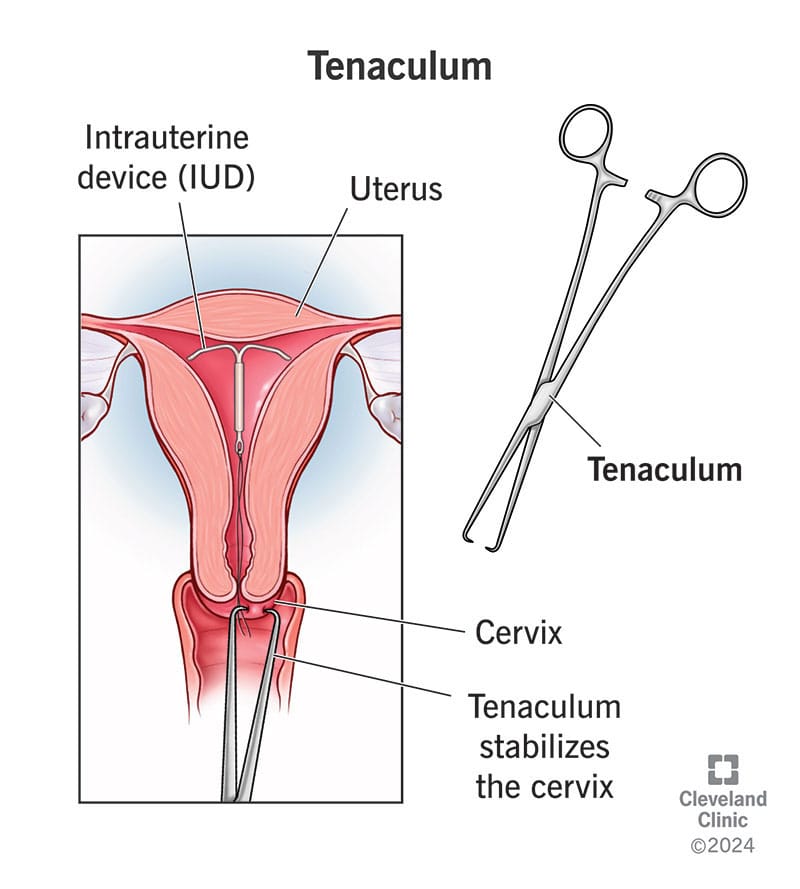

Inserting an IUD is accomplished by holding the vagina open with a speculum, gripping the cervix with a tenaculum (like pliers, but pointy), plumbing the depth of the uterine cavity, and passing a tube containing the device through the cervix.

The cervix is densely innervated with sensory, sympathetic (fight or flight), and parasympathetic (rest and digest) nerve fibers. Some of these nerve fibers come from the vagus nerve, which controls blood pressure, heart rate, and some upper gastrointestinal functions; other nerves come from nerve bundles in the sacrum, or tailbone.

So a painful stimulus in the cervix is not just quantitatively greater, but qualitatively distinct from a similar stimulus applied to the hand, for example. In addition to a pure “pain” sensation, many women report cramping, nausea, shaking, lightheadedness, and other symptoms far from the cervix itself.

Understandably, it’s difficult to alleviate this multifaceted pain response. UpToDate (your doctor’s favorite online reference) lists no fewer than five different modalities for pain relief that could be used during insertion. These range from NSAIDs like ibuprofen, numbing the cervix directly, taking medications to soften the cervix, and general anesthetics.

Nearly all have fairly mixed evidence for use; the best options seem to be injecting some lidocaine into the cervix (which is still an extra injection, which hurts) or coating the cervix with a numbing spray (although the usual sprays are difficult to apply to the cervix).

None of this is new information; there is plenty of coverage in the media about IUD insertion pain, including several pieces in the New York Times, the Outline, and the Wall Street Journal. Nevertheless, it was only earlier this year that the American Council of Obstetrics and Gynecology came around to the idea that some form of cervical numbing should be available, or at least discussed. This means that most women today will have gotten an IUD when pain control was very much left to the preference of their Ob/Gyn.

Provider Preference and Pain Control

It’s likely that part of the hidden curriculum of OB/Gyn training (and probably for most other medical professionals) is dedicated to comfort with patient pain. In many ways childbirth is at the center of the specialty, a biblically uncomfortable process. And even non-medical people don’t treat the pain of childbirth as unusual or a sign that something has gone awry, as long as the mother and baby are healthy afterwards.

This professional comfort-with-discomfort is probably best illustrated by comparing the progress in instruments used by OB/Gyns compared to urology, a medical field also closely concerned with matters of the pelvis:

When one specialty has moved from rigid steel tubes to fiber optics, and the other has gone from rigid metal to rigid plastics, there are likely cultural (and not just technical) factors at play.

Hormones (and not)

After the IUD is in place, pretty much all patients can expect a week or so of symptoms. There is generally a fair bit of cramping that persists after the insertion and continues for a few days - 86% of people receiving an IUD take something for pain control, with authors recommending 2 to 3 times the usual over the counter dose of ibuprofen. Bleeding generally lasts for 4 or 5 days, requiring 3-4 pads per day (about half a soda can of blood per day).

Once patients are past this initial unpleasant week, there is still a question of how they’re going to like the new device. Copper IUDs result in about a 50% increase in monthly menstrual bleeding, which may cause symptoms of iron deficiency anemia in some women. Since nearly 40% of women in the US are already iron deficient, many women are already at elevated risk of anemia (although they may not know it).

Apart from bleeding, the other issue is how women will feel with the different hormonal profile of IUD-based contraception. The serum concentration of progesterone from hormonal IUDs is about 1/5th of that of other progestin-containing birth control, but it can still lead to acne, weight gain, nausea, and mood changes.

Further, women getting an IUD may be switching away from estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives, which can help with menstrual cramping, acne, menstrual symptoms, and other issues. That is, these women may experience both adverse hormone effects from the new hormones from the IUD, in addition to the lack of the hormones they are no longer taking.

This is not to say that everyone feels worse on IUDs…a lot of women feel better! Notable swole woman and author Casey Johnson felt stronger on her hormonal IUD after switching from the estrogen-containing NuvaRing. But nearly everyone will experience some undesirable side effects, which may take many months to resolve.

It’s the Healthcare System

Most people are getting an IUD with a goal of having sex without getting pregnant. However, even if a person is dead-set on getting an IUD, and is sure it’s the right thing for them, the average appointment wait time is 42 days for OB/Gyn.

This means having to use another birth control method for more than a month before even seeing a provider to discuss an IUD. The wait time might ultimately be even longer if insertion is scheduled separately from the consult, sometimes to coincide with menstruation.

These delays are doubled for women who decide they don’t like their IUD and want to get it removed. Between 13 and 36% of women will have their IUD removed within a year of insertion, and wait times can be just as long.

Further, some providers will hesitate to remove an IUD placed by a different provider so if the initial provider moves or your insurance coverage changes, finding a second willing provider could be even harder.

While IUD insertion and removal is not the greatest care delivery failure of our healthcare system, it may be a particularly salient experience for young, otherwise healthy women. For many young women, reproductive care may be their only regular point of interaction with the healthcare system; nearly a third of women consider their OB/Gyn to be their primary care provider. Frustrations at the healthcare system as a whole are viewed through the lens of this particularly convoluted corner of family planning.

Final Thoughts

IUDs work very well - they prevent pregnancy about as well as tubal ligation, last a long time, and many women are pretty happy with them. About 10% of women in the US currently have a long-acting contraceptive device (either an IUD or implant). IUDs are the right choice for some women, and even the pain associated with insertion could probably be made more comfortable with greater adoption of local anesthetics and other procedural refinements, such as replacing the metal tenaculum with a strong vacuum.

But bring up IUDs in a large diverse group of women? You’ll hear about pain (and inattention to pain), bleeding, cramping, hormonal side effects, scheduling barriers, and more. While the rate of medically significant complications is indeed low, overall negative perception is fairly high. Some of this is probably due to the primacy effect, where the first part of an experience (painful insertion) feels more memorable or important than latter parts. Some of this is also due to fundamental pain bias on the part of providers - the belief that others consistently exaggerate their discomfort, which shapes both the way pain is managed and what pain is seen as worthy of study.

In my own practice, I do my best to elicit my patients' goals and present an array of contraceptive options that would seem to meet those needs. Some people don't want to take a pill every day, feel better with minimal or no hormones, and are not dissuaded by the prospect of some significant discomfort; an IUD might be a good choice for them. But generally we’re fortunate that there are a lot of effective birth control options out there (although nothing reversible for men, yet) and I don’t think anyone should be getting an IUD without a good look at the entire menu.

Brian Erly is a primary care physician working in Denver, CO. He does not have a uterus, so many affective aspects of gynecology are inaccessible to him, although he does his best. Tell him about it in the comments!