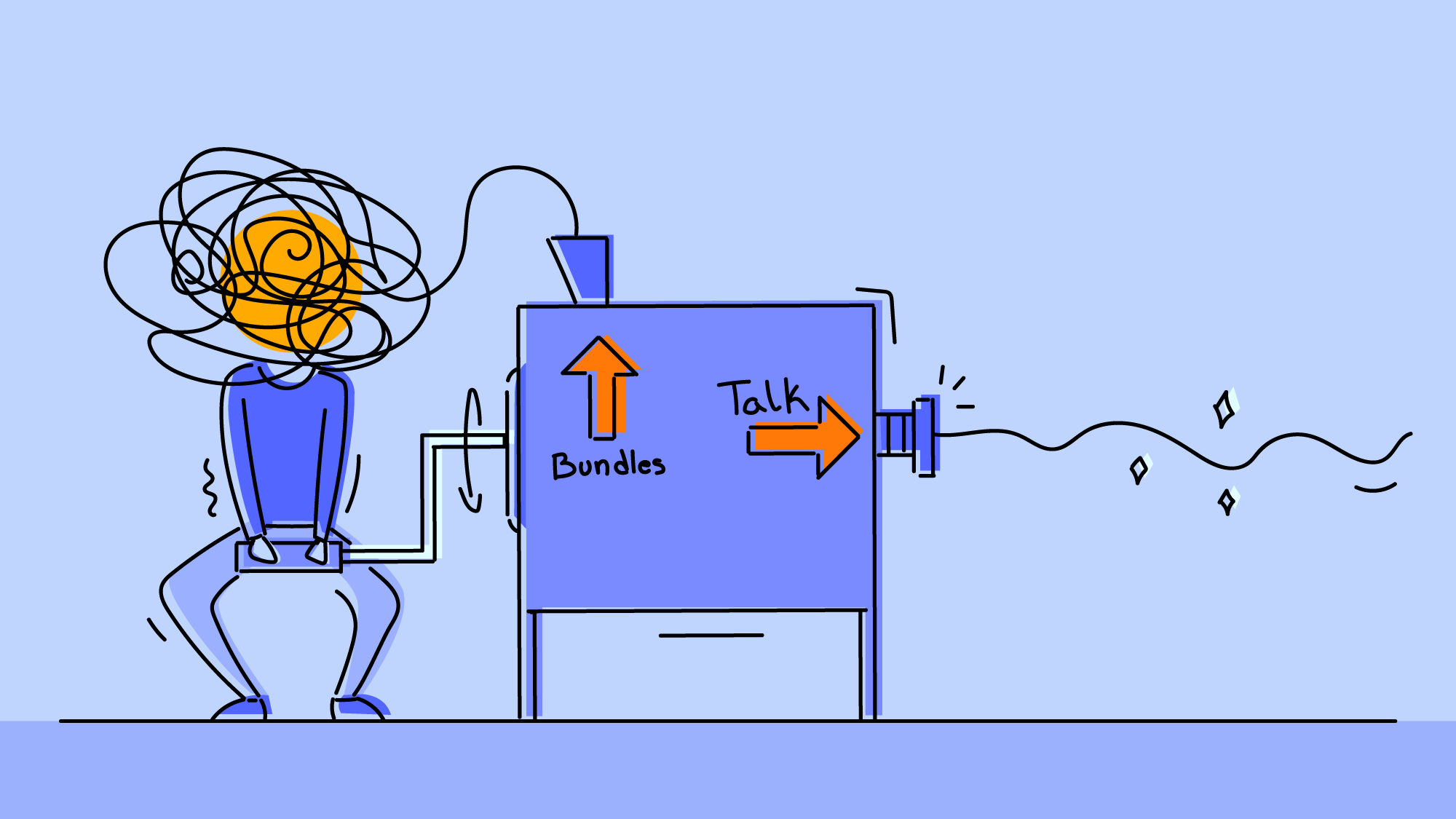

Pushing Bundles Of Thoughts Out Your Mouth

Here is what it’s like to think:

Here is what it’s like to talk:

On some level, the entire problem of communication is the difficulty of pushing complicated bundles of inter-related thoughts through the low-dimensional space of your mouth.

In trying to convey a complex 3-dimensional object through a series of 1-dimensional etchings, not only are you forced to straighten out complex curves into straight lines, you lose a ton of information about the relationships between the lines.[^1]

This has various difficult consequences.

Often, when I’m asked to give examples to support a point, there’s 6 different examples that collectively are the reason I believe that thing; they each add a bit of weight to my beliefs, but none of them are dispositive. When speaking, I have to pick a single one of them to linearise, and so my claims feel unconvincing even to me.

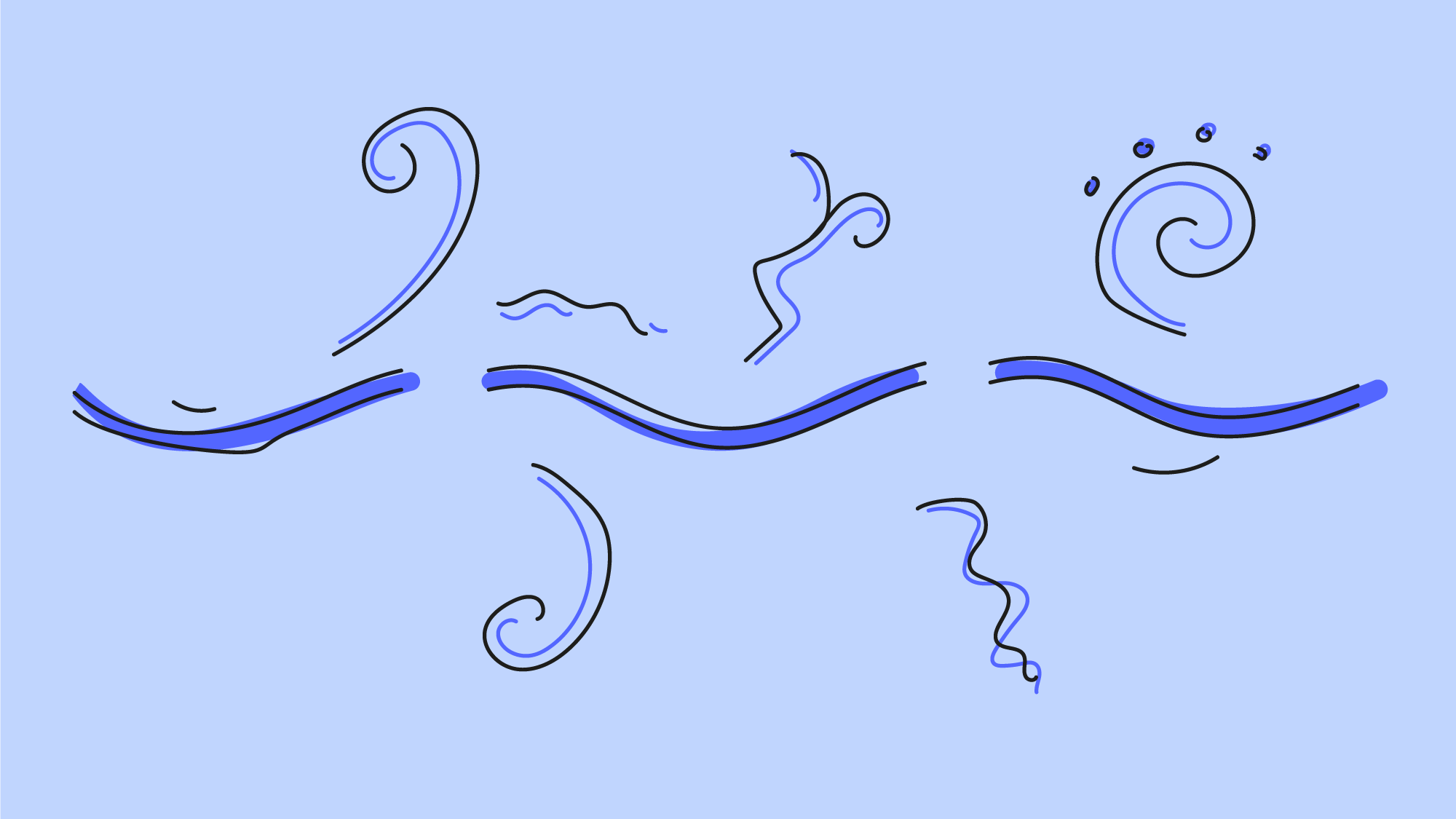

Similarly, the decision of whether to include all relevant caveats is excruciating. If you have this bundle of thoughts and caveats:

You only have a few choices: express the main branch without the caveats – for a certain kind of brain this is EXCRUCIATING, since you know that you're conveying something simplified and inaccurate:

Talk for a really long time, expressing the point and then all the caveats, by which point your listener has probably forgotten some of the point, and struggles to connect the caveats to the points.

Or explain each caveat when you reach it, which (realistically, usually) means you never get to the end of the main point, you run out of time or get derailed explaining the caveat to Step 1

(Pop quiz: Do you remember the shape of the original diagram, now? I certainly don’t).

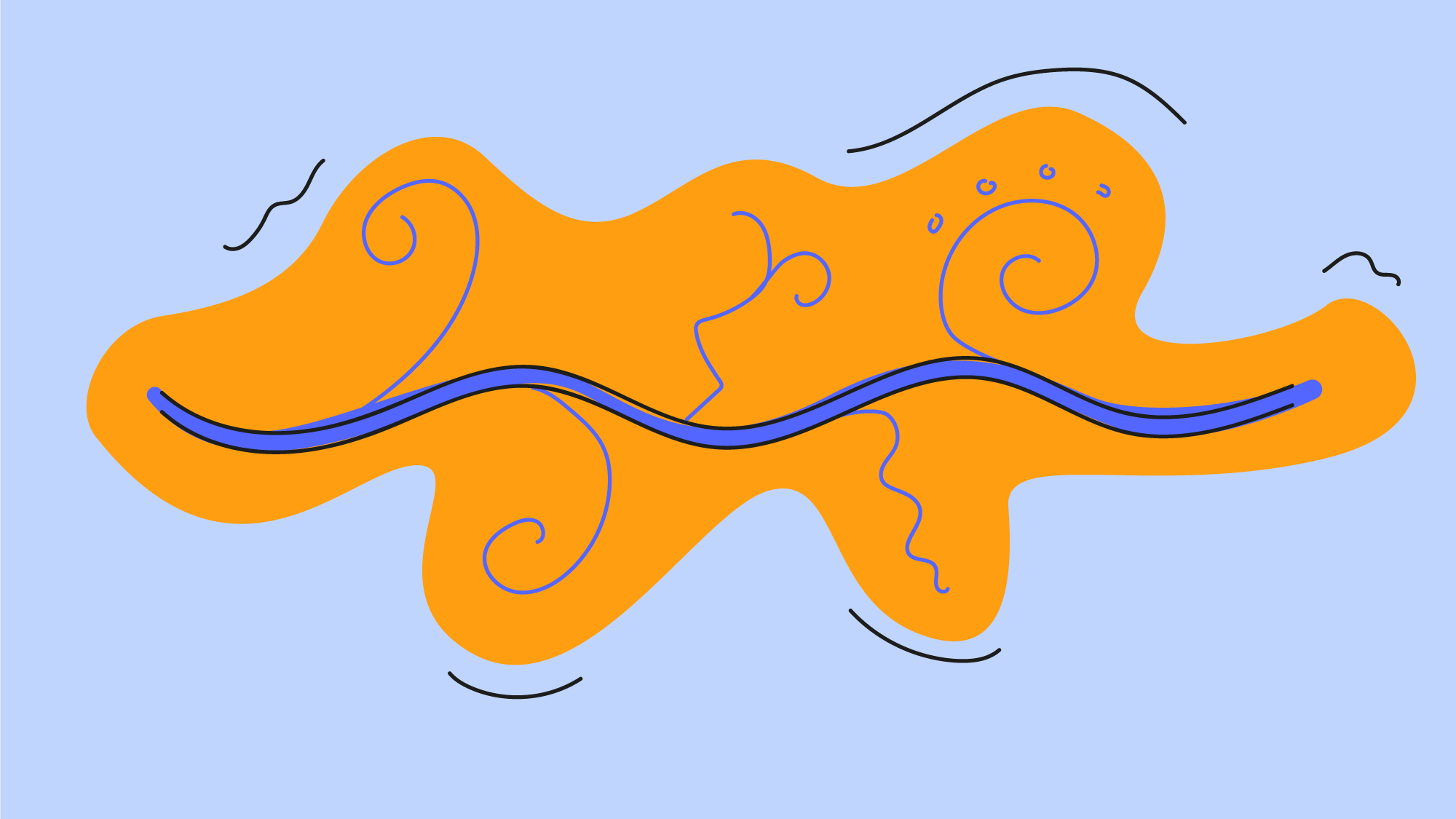

Is there anything to be done about this? The philosopher Kalid Azad has written about the benefits of giving an outline first and details later:

It seems logical to assume we can present facts in order, like transmitting data to a computer. But who actually learns like that? I prefer the blurry-to-sharp approach

[Perhaps you've noticed – though equally, perhaps it isn't really noticable – that this is what I’ve tried to do in the structure of this post: focus in from blurry to sharp].

In my schematic, Kalid’s method might look like this: first giving the overall shape of the thing, and then adding details inside it:

I think this is probably a good approach to communication, though as a person who doesn’t like saying untrue things it is very hard to give the outline knowing that it doesn’t really convey the whole truth.

Incidentally, this model is one reason I don’t believe my thoughts originally exist in language. A friend recently suggested that all his thoughts were verbal, and that if he had lived in a pre-verbal time he’s not sure how he would have been able to think. I had an intuition that my thoughts are non-verbal, but it was very hard to describe what they are -- it’s not like they’re all visual, or composed of numbers, or something.

I do have an inner monologue which is composed of subvocalised words, but I think most of my thoughts exist in some direct way as bundles of concepts, structures that can exist kind-of-spatially in awareness rather than in word. Which is why they're so hard to put into words in order to push them out my mouth.

[^1]: relatedly, see Scott McCloud on cartooning on page 45 / PDF-page 52 here